Read Dean’s advice on research, budgeting, construction and location scouting, and benefit from his years of experience!

Excerpts taken from the books Conversations with Dean Tavoularis and Working cinema : learning from the masters.

"All of a designer's professional relationships are important, and none should be neglected, but if I had to name one that was first among equals it would be that with the director. The director is the one individual with whom there must be the most complete rapport, the highest level of communication. If there can be said to be two camps in the making of a film - the director's side and the producer's side - the production designer definitely belongs in the director's camp, although taking care not to go over budget.”

"The producer always wants a detailed budget at the outset before the set designs have been sufficiently developed so that I can really assess the true costs; and so I never make a budget until they scream for it. The more I can delay, within reason, the more accurate I can be in submitting the budget. The set designs must be finished before I can make an intelligent estimate of the costs of settings for a given film.

Budgets are always an influencing factor, but the designer should not be crippled by thinking first about the cost. We look for solutions to dramatic problems, then weigh the costs. Obviously the designer cannot solve set problems with a blank check, but if one is subconsciously aware of realities there will be found a solution that meets the needs of the film and fits within the limitations of the budget."

"The production designer may need to defend himself or herself and the work from the expedient. If others argue for a solution that is stupid, or merely convenient for somebody else, he or she may need to counter that this solution is a more beautiful or evocative setting for the drama. If the cost is slightly higher and the scene is important enough to justify the extra expense, so be it.

For the scene in The Godfather where Michael assassinates Sollozzo and the cop McClusky, we spotted a fabulous Italian restaurant up in the Bronx. When I sat down together with the owner I Imedietaly noticed this disgusting linoleum floor that was covering the whole restaurant. I asked him what was under it and he said he didn’t know. So I walked around a little and saw that back by the bathroom where the floor wasn’t covered up, there was this beautiful mosaic. I asked the owner if we could remove the linoluem and shoot the real floor. I remember it cost something like an extra $8000 to do all of that, and of course, the producers said there’s no way they would spend that much money on a floor. “The guys are at the table, he shoots them… You don’t have to see the floor” they argued. I said to them: “The whole fucking room is on a floor and you’re going to see it. It exists and you have to deal with it.” Finally the producers relented, and when we took the cover off there was this beautiful tile floor that the owner of the restaurant of course wound up keeping. You certainly see it well enough in the film, especially in the last shot when the camera is high up and looks at the scene of the murder."

"Research is the sparking point that gets you going, particularly when dealing with a period film. The moment I have read the script and talked to the director, I begin to do research because ideas come from what I discover at an exponential rate, with ideas sparking more ideas. I pore over old photographs from archives, look at paintings in museums, and read literature about the period in which the story occurs.

On the "Godfather II", for example, the research pictures of the immigrants at Elis Island in New York in 1912, old photographs of Little Italy, evoke powerful emotions. The images are very real, very poignant, and the production designer wants to capture that ambience for the film. Seeing the pictures and reading about the immigrants is a very emotional thing."

"Getting into the locations of a story really means getting into the life of the film itself, getting those feelings about ambience that should be given visual forms.

Back in the days when I designed Bonnie and Clyde t here were no location scouts - the art director was in charge of all that. So I went to Texas to scout for locations, and a lot came from driving around those Texas towns. The film takes place during the Great Depression, and when the Depression hit those places, they just froze. I would go into shops down there, like a men’s clothing store, and they still had boxes with men’s shirts in them from the 1930s, like they’d just locked up the place and left.

For The Godfather, it was hard to gain access to the real locations that the mafia frequented without knowing somebody, so Francis gave me the address of a friend of his who was a director and could show me around Little Italy. I went to his apartment and this young guy opens the door: it was Martin Scorsese. He was able to show me the Italian social clubs and the cafes where the mafia would hang out, and we spent the day visiting Lower Manhattan together. It helped give me an idea of the kind of places the Corleone family would frequent."

"We always prefer to adapt some existing location for major settings rather than to build it from scratch, at least when period films are involved. An important consideration in location selection is whether other scenes can be photographed there. One needs to pick the main day's shooting in the same part of town where there are other shots to be picked up, out of context. At every location we discuss how every aspect of it may be utilized to shoot as many scenes as possible in as brief a period of time as possible, commensurate with quality.

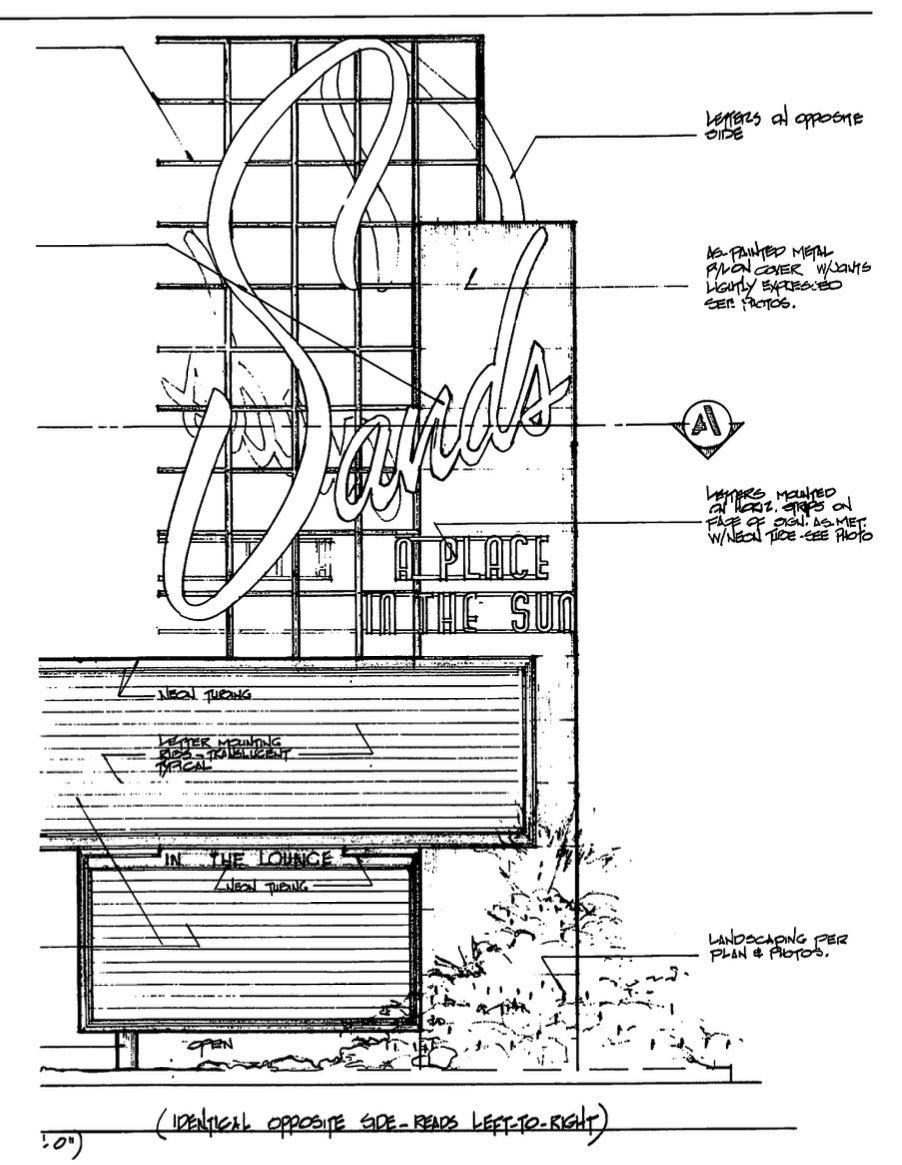

And, at every location, I take photographs and measurements that would enable me to make drawings that could become blueprints for set construction. Set design and construction cannot be considered something that applies only to interior settings to be photographed on a studio sound stage, as if they were different in kind from location cinematography. In practice, much of production design work consists of adapting existing structures on location with partial sets.

Whenever I go to a location I look for specifics. I look at interiors and ask myself whether it would be as effective and less expensive to build the sets. The smaller the setting, the more likely it should be built on a stage. A lot depends in making this decision on the dramatic importance of the setting. If a scene set in a bar takes up twenty pages of manuscript, we will certainly build it because it will shorten production time to have control of all the visual elements. On the other hand, if the drama fills twenty pages of manuscript in a railroad station, the cost of building that station might be so exorbitant that going on location and making adaptations to a real station might be the prudent choice. The production designer must always want to spend his or her budget funds intelligently, and well. The bottom line is not cost, however, but the quality of the film.”

An important part of the job of production designer is to argue for quality in set construction. For example, I was working on a film where the drama takes place for the most part on a large yacht. I wanted to use real teak and real mahogany for our set and not cheap pine that has been textured to resemble teak and mahogany, and there are good reasons for this. Most of the story is told in the small environment of the ship, and the viewers will have a long and close look at the setting and will eventually detect what has been faked - to the detriment of the credibility of the film. Teak, for example, turns from chalky white when dry to dark red when wet, and that will not happen with pine. This is a film about the sea, with storms that soak the ship, and the wood must respond authentically when drenched.

As I said, an important part of this job is to argue and win those disputes about production quality when dealing with those who would do things with only cost in mind. This issue is usually faced when dealing with the production department, an arm of the producer. If need be, I will tell the producer 'It's not your job to tell me to use pine instead of mahogany. It's your job to see to it that I don't go over budget. As a last resort, when there is an issue of quality I turn to the director, but I do so only as a last resort."

"The production designer is responsible for making the actors feel comfortable on the set. The sense of smell does not show up on the screen, certainly, and yet scent is important to playing a scene. The actor or actress should be immersed in the scenes in which the drama is supposedly taking place rather than in the smells of paint and varnish that usually surround a newly finished set. In the grocery store scene of "The Brinks Job", we built the set and spent the whole night dressing it to look right for the camera. Then, just before principal photography began, we crushed sprigs of garlic, oregano, and paprika around the set so the context would feel right to the players in that setting. The production designer must not overlook anything in the broadest design of the set or the finest detail of decoration that may contribute to a convincing performance.

Props are often used as a point of dramatic focus in the film, and actors and directors love props to handle to ward off nervousness and add topical interest. I often put things into actors' pockets to make them seem more human and credible. Why shouldn't a screen character have loose change and keys in his or her pockets?"

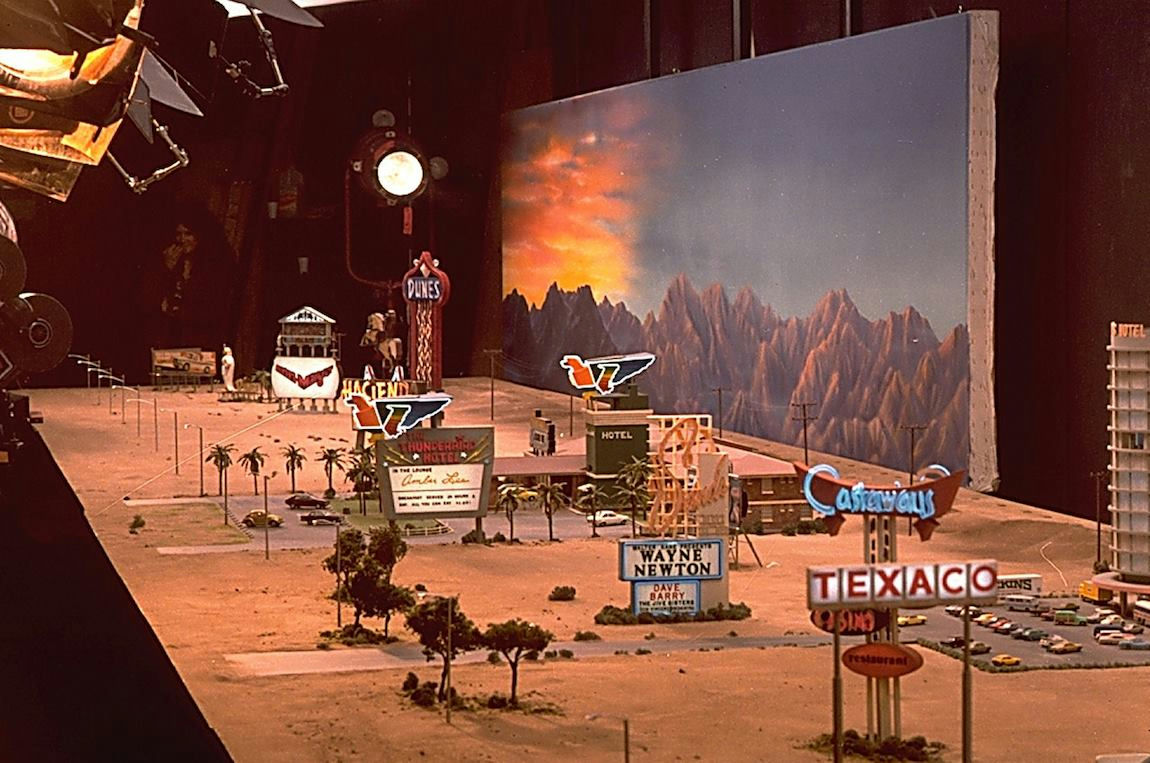

"Consistency is the key word here. The important thing for any production designer to do is to look at the film and solve its most difficult problem first and then apply that solution to all the other problems.One cannot solve the easy ones first and then come back to the hard problems and expect aesthetic consistency in the film.

On One from the Heart, as usual I decided to tackle the hardest problem up front, which was the scene near the end of the film when Fred Forrest drives to the airport to try and catch Teri Garr. When we talked it over with Vittorio Storaro, he was under the impression that we would do that scene with process shots of the road between Las Vegas and the airport, then put them in the background with Forrest driving a car in the studio. But I told him that if we did that, the process would be trying to tell people that this was a real car on the street, while nothing else in the movie was real. So we needed ot find a way to do that shot completely in the sutdio. It wasn’t for any purist reason, but because I felt there should be the same solution for every problem rather than a different solution for each problem. We needed to take one idea and carry it through the whole film."