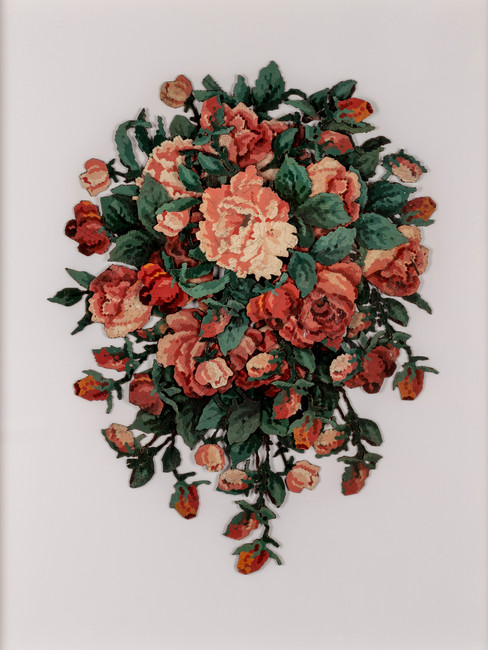

Raze (rise), Hand cut and collaged linoleum flooring, glue, wood, 69” x 43” x 2”, 2022; image courtesy of the artist

Artist Christina P. Day takes us on an archive dive into the story of a product

I have long had a fascination with flea markets; the “last call” for an object before it ends up in the trash. As an artist, prompted by a growing curiosity I had about broken pieces of linoleum that I had found in a junkyard, I began a research journey to track their origin. This article explains how I used different resources at material archives between the United States and the United Kingdom to understand the journey of how something gets made.

In my teaching life, I am a Professor of Fiber at Maryland Institute College of Art in Baltimore, Maryland. A few semesters ago, I created a project about locating one’s art practice on a continuum or timeline. The assignment asks students to use recent work as a launch point backwards in time to cite references and establish a kind of creative family tree. The questions to start: What are the design references inside your work? Research those similarities to find the inspiration behind those and so on, until you are reaching so far back that you cannot easily find answers. How far back can you go to find the beginning? This self-reflective research can head in some surprising and revealing directions.

During the pandemic I turned this project on myself, concentrating on flooring materials as part of my artistic practice. The research journey took me through several archives to understand why a material like linoleum is now finding its home in the waste stream. I suddenly found myself walking in the earlier footsteps of other researchers, historians, and discovering an interesting production history.

Roser, Hand cut and collaged flooring salvage, wood, paint, glue, 26 1/2” x 20”, 2019; Push, Hand cut and collaged flooring salvage, wood, paint, glue, 10 3/8” x 13 5/8”, 2019; both images courtesy of the artist.

To begin this homework I read Cheap, Quick & Easy: Imitative Architectural Materials, 1870-1930 by Pamela H. Simpson. I had always been interested in mimicry but had never read scholarship on how this shows up in architecture. The book cited the history and innovation of ornamental sheet metal, concrete block, embossed wall and ceiling coverings and linoleum. The idea of a faux finish was of immediate interest to me.

When I came across this picture of female factory workers piecing mosaic linoleum in Simpson’s book, I suddenly had a lot of questions.

I used my recent sabbatical year to set up a series of archive visits so I could continue to explore the answers to questions like:

Who made this? Why does linoleum appear to be pixelated? What was it made of and why does it fall apart like this? And for the love of all things, who in the world thought this pattern was a good idea? Though all this process appears to be buried by history, can I actually visit any of this in person?

Female factory workers piecing together mosaic linoleum, factory unknown;

image courtesy of Kirkcaldy Museumcourtesy

Soda House Archive, Hagley Museum and Library, Wilmington, Delaware, United States

In the fall of 2022, I received an Exploratory Grant from the Hagley Museum and Library, a patent library focused on American innovation and invention in Wilmington, Delaware USA. For a week, I took on a very different type of work, that of a researcher reading in a quiet library. Instruction manuals from 1905, pattern trade books, and historical accounts of the linoleum trade in Kirkcaldy, Scotland, Kearny, New Jersey and Lancaster, Pennsylvania were un-shelved for me to review. Reading and looking at what artifacts remained from the early part of this production story helped me tune into a stream of information, like searching for a working channel on an AM radio dial. I felt as though I was waving to someone else through space and time. As I viewed lantern slides from the Armstrong Flooring Company of Lancaster, PA on a backlit light box, I observed the tight choreography of a factory production floor, the workers walking a quality check in their factory overalls on a newly finished flooring pattern. The material was gorgeous, a result of an arduous physical printing process, now lost to time. What we find today and try to peel off our hardwood floors is a distant cousin to what is in the picture. How did this happen?

Left: Armstrong Flooring Company factory image, quality check walk, date unknown. Right: Armstrong Flooring Company, printed inlaid linoleum process, date unknown; Both images courtesy of Hagley Museum and Library

Sidenote for those who might seek patent history for film projects- Hagley has an outstanding and incredibly deep collection of nearly 5000 patent models that they rotate in exhibition displays. This venue is worthy of an article of its own. If you find yourself in Wilmington, Delaware it is entirely worth the effort to reach out to Assistant Curator Chris Cascio for a behind the scenes tour. If you are abroad, look at the models that are online! You can thank me later.

My time at the Hagley Museum and Library taught me how to navigate archives. It is obvious perhaps that the more specific you can get with names, dates and key words, the more accurate the resources will be. This required several rounds of reviewing materials which helped to hopscotch my research to a different location abroad- the birthplace of the trade. Not surprisingly, this is where the picture of the female factory workers piecing together flooring was from: Kirkcaldy, Scotland. I resolved that the Kirkcaldy Museum would be the next waypoint on my journey and contacted their Curator Lily Barnes to arrange a visit.

Kirkcaldy Museum; image courtesy of Christina P. Day

Left: Mosaic linoleum fragment; Right: Printing tool. Viewed at Bankhead Archive for Kirkcaldy Museum; images courtesy of Christina P. Day

The Kirkcaldy Museum in Kirkcaldy Scotland houses over 6000 samples of linoleum and related artifacts to the trade. It was established in 1925 by John Nairn, grandson of the Kirkcaldy-based linoleum manufacturer Michael Nairn, and houses a large painting collection of Scottish artists and a permanent exhibition covering the town's industrial heritage. The archive is housed in a former Amazon Warehouse (given the trajectory of linoleum, which was created during the industrial revolution, I found this to be deeply ironic). Because of what I had learned at Hagley, I was able to be more specific about the samples I requested to see in Kirkcaldy. For two days I reviewed hundreds of samples, books, images, tools, and ephemera. I was at the epicenter of the topic and was able to view things that no other museum would have: the factory printing tools, large samples of mosaic and inlaid linoleum, original images of factories processing the material, and more. I began to understand the real scale of linoleum production and how complicated it was. At its peak Kirkcaldy had six competing companies producing linoleum within blocks of one another. Knowing this had me re-evaluating those broken pieces of flooring found in the junkyard in northeast Philadelphia.

The Winterthur Home of the Winterthur Museum, Garden and Library

Left: Bearing Witness exhibition at the Winterthur galleries; Right: Rare Books at the Winterthur Library. Images courtsey of Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library.

Upon returning to the United States, I received a 2023 Maker-Creator Fellowship at the Winterthur Museum, Garden and Library in Wilmington, Delaware where I continued to read on the design history of linoleum. I was additionally blown away by the incredible mashup of architectural and interior design styles present in the mansion house. Every room (of which there are 175!) and hallway is a cabinet of design curiosity and an education in how American rooms looked and felt during and after the Victorian era. It is a spatially puzzling place for those in the business of seeing and making.

By lacing together information I picked up from visiting these three major archives, I learned how linoleum came to be. Understanding the history is helping contextualize decisions I am making in my sculptures. Studying the history of linoleum has formed a foundation upon which my most recent body of work is based and made for a fascinating research dive during a crucial year of studio work and reflection. Nearing the conclusion of my sabbatical I am left with several questions that I would encourage anyone working in a design or art adjacent field to consider. I can attest that in attempting to answer these questions, one can find inspiration, intellectual sustenance, and the next steps on one’s own creative journey. There are archives out there that are waiting for your questions!

What are the repeating themes in my approach to work?

Is there a historical precedent for the decisions I make?

What are the “givens” or the things we take for granted in a scene, or in real life, that put our audience in the appropriate time and place and mood?

Have we dedicated enough attention to these details?

Telegrapher, Hand cut and collaged and salvaged linoleum, wood, paint, glue,

polyacrylic, 26”x 30.5” x 2.25”, 2023; image courtesy of the artist

About the Author

Christina P. Day’s art practice recontextualizes roles related to material lifespan: designer, fabricator, owner, maintainer. Her improvisational building language stems from textile design strategy and is focused on the conversation of material as content. Her work takes form in architectural installation, surfacing methods, textile pattern logic and physical match finding. Day is a full-time faculty member of the Fiber Department at Maryland Institute College of Art (Baltimore, MD), where her teachings focus on cloth production methods and experimental fashion. Recent exhibitions and research on material history have been completed at Museum of Contemporary Art Arlington (Arlington, VA), Commonweal (Philadelphia, PA), Winterthur Museum, Garden and Library (Wilmington, DE), Hagley Museum and Library (Wilmington, DE) and Kirkcaldy Museum (Kirkcaldy, Scotland). She maintains her home and studio in Philadelphia, PA.

For more information, please visit www.chrissyday.com