Alex Schaller's work has recently been screened at festivals including the Toronto International Film Festival, SXSW, the Berlinale, the Tribeca International Film Festival, and the Sundance Film Festival. I caught her between projects in New York this cold February to chat with her about her experiences working in independent film.

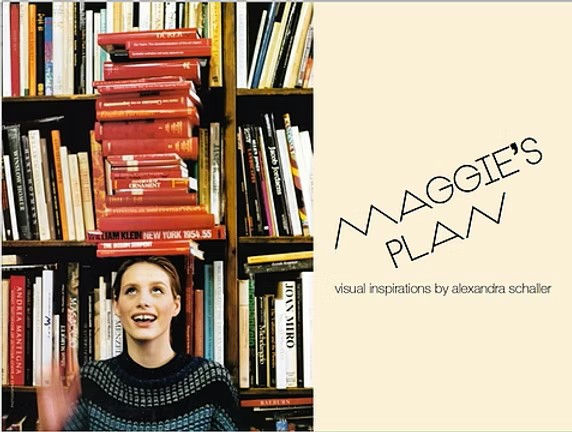

PDC: First, congratulations on your films at Sundance - you had two screening, Little Men was in the Premieres section, and Maggie’s Plan was part of the Spotlight section, having premiered at Toronto. Both films take place in New York, but have different stylistic edges. Maggie’s Plan is brighter, with an air of quirk, while Little Men leans to the real. How were those born out of your collaboration with the directors?

Alex: Thank you so much. I was very lucky - both directors really trusted my creative sensibilities and instincts, but it was definitely a big collaboration with each of them. On Maggie’s Plan I also worked really closely with the DP and costume designer. You’ll see that many of the colors are complimentary between the production design and the costumes, which was a deliberate choice.

They are two very different movies - Maggie’s Plan is a comedy and we wanted to push that and heighten it to create very specific characters, while still keeping it plausible, grounded and relatable.

In Little Men, the style is much more naturalistic, Ira was influenced by a lot of classic french movies from the 70s and 80s, so there was a much quieter, romantic style to the film. Almost a painterly quality. But, because it’s a film with two kids as the leads - which is very different from Ira’s other films - we had the idea of elevating certain scenes from the kid’s perspectives and selectively adding strong punches of color, particularly as one of the children is an artist. A lot of the design of that film was based around a child’s interpretation of the world so at times we chose to draw attention to certain colors or textures - those things that when you grow up you remember from being a kid. So there’s a dichotomy in the film between bright and colorful moments and much more muted, naturalistic scenes with the parents but Ira and I wanted to make sure they blended together seamlessly - and figuring that out together was a lot of fun.

PDC: You were involved in Maggie’s Plan for quite some time before production began. Were you able to use the time you had to develop the style for the film and begin collaboration?

Alex: Yeah, with Maggie, I came on a long time before we started shooting. I was attached, and then the project pushed for various reasons - so there was a comparatively long period of time for us to develop the characters and the color stories for each of them. Maggie, played by Greta Gerwig, is a much more colorful, whimsical soul than pragmatic Georgette, played by Julianne Moore, who is much colder and more severe - so her world is much more monochromatic. That was a lot of fun to play with, and there was a lot of opportunity for that because it was a comedy, so we could really heighten it.

PDC: How did you begin that collaboration? Did Rebecca initiate the conversation?

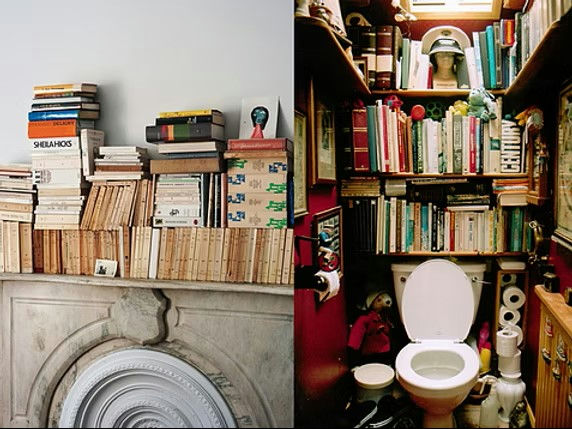

Alex: Rebecca is a very collaborative person and it was really inspiring to work with her because she has a strong creative voice and values her creative department heads in their own right but also as a collaborative team. I came on three or so months before hard prep started and from that point on, we aimed to have a weekly meeting about the design. I would go to her office and present new pictures every week - which was a huge amount of work to do before “officially” starting - because I was juggling it with other jobs I was working at the same time, some of which were out of town. I spent hours in the library, where I was pulling a lot of my pictures, making these moodboards. Rebecca comes from theatre like I do, and loves tangible things, so I made her real, physical boards instead of digital ones that included images but also fabrics and tile samples - lots of textures. We would put all this around her office, which became an “ideas station,” and she would have other meetings for the film in that room. Everything grew and built from there until the room became a cocoon of the movie because we kept adding and adding. I think it was inspiring for everyone to be able to “stand inside it” so to speak.

I’d never worked that way with a director before, which made it very special. She’s a director with high expectations (in a good way), and knowing you have that weekly meeting means you have to keep thinking about the film. The movie’s always on your mind. It keeps things building, and by the time we started hard prep and my crew started showing up, we were ahead because so many decisions were already made and our goal was clearly formed in our mind. It sounds like that should be the way it always works right? But we never get to do that on lower budget movies so it was a very unique experience.

PDC: Did you have that kind of time with Ira?

Alex: Not quite the same amount of time but the movie did push so we got a little more time than we originally thought. I was working on another film at the time, but I did put together a lookbook for his film for the interview. I knew that because it was Ira Sachs, he was probably talking to a lot of very talented designers, so I tried to create a comprehensive lookbook for our meeting that laid out all the main strokes of how I imagined the film. From the beginning, I felt strongly that there should be a kid world and an adult world, but that they shouldn’t feel too apart from each other and Ira agreed with that. Ira is a remarkable cinephile, so the research period was our watching movies with the DP and costume designer and talking about those films. Ira would also bring photography books to the office and we would leaf through them. I also feel that we were able to capture the essence of the movies he was inspired by with the cinematography so everything came together nicely. It was definitely a smaller period of development, but it was also a much smaller movie.

PDC: I know that Ira Sachs prefers to keep his teams very small, he likes the intimacy of a smaller budget. But that can put a lot of strain on what you as a designer, the less money there is, the fewer people and resources you have, though a director’s vision often doesn’t get diminished. Do you ever feel like the directors vision of how they want the film produced and what you have to do to create the vision are at odds with each other?

Alex: I’ve been so fortunate that my sensibilities often align with the directors I’ve been able to work with. If you’re working with a director, like Ira or Rebecca, who has made many movies with different budgets, different sized teams, different actors, different styles, they come to expect a certain level of professionalism and finish. That’s what’s hard, trying to achieve the perfect level of polish on a smaller budget. Luckily on Little Men the line producer, Jonathan Montepare, was an amazing human being and such an understanding and supportive ally. He was interested in the creative aspects of the film, so he tried to facilitate with labor and a little bit of money where he could. The location manager was also really great and that goes a long way for us designers! One good thing is that Ira is able to pull in a very talented and professional crew and working with pros definitely helps when working with a smaller budget.

PDC: Did that turn out to be one of your most important, and maybe surprising, collaborations?

Alex: Yeah, he was great. And as I mentioned, the location manager, Jillian Stricker, was also amazing to work with. Everyone should have her on their movie! She had a very nuanced and sensitive understanding of the script, so she’s really looking at places based on script motivation, as opposed to looking at places and saying “eh, this could maybe work, they could fix this.” Not that anything was “walk in and shoot” - what Ira wanted was very specific - so we redressed most locations 90–100%. But she worked collaboratively with the art department as someone who understood the budget and script and story. Whenever we would walk into a location scout we were never scratching our heads asking “what the hell is this for?”

PDC: Were there parts of the film you wanted to have more input on? Were there films where you experienced a lack of collaboration?

Alex: I’m a pretty vocal person so no, I insert myself, haha. Though there’s a certain thing to be said about the fact that once you start shooting a film, that relationship between the director and the DP can be alienating. Especially when you’ve been working with a director so very closely up to that point. Though, the DP from Maggie’s Plan, Sam Levy, who is an amazing person, once told me “don’t worry, I’m looking out for you - what’s good for me is good for you.” And that’s stuck with me ever since because when you build something together, it’s true.

PDC: The DP can become an important supporting position for a PD on a film set. They are the ones that go into production and put what you made on film, while you’re often not there. Often and even getting a lunch meeting is difficult -the director is making critical decisions with the AD, or working to get the actors into the right headspace, and you can’t get a thoughtful opinion from them about something that’s changed, so going to the DP is the next conversation.

Alex: Yeah, you just have to trust them. Everything is in their hands when they’re shooting. One special thing about the collaboration with the DP on Maggie’s Plan was getting to be involved in the discussion of the color camera tests we did in prep. Because the paint colors were decided so far in advance, we had the time to shoot some tests with the actors and I was invited to a screening of those tests so we could see how our practical color choices read on camera against the actors. To be invited to that is so rare in independent film. He gave me the opportunity to understand how our choices were going to look in the long run and we got to talk about it. It would be nice to be more involved in that process so we can change things that aren’t working and expand on the things that are. Particularly as so much of our time is spent on developing color and texture.

PDC: What a fantastic opportunity. In independent filmmaking, the designer is often left to be a bit of a rogue position, there’s a lot of decisions we make without the involvement of any of the other team members that do end up effecting the way the film is made, and it would be better to make them collaboratively.

Alex: You know, as an aside, I went on a mini artist residency called SPACE on Ryder Farm. One great result was that the directors came out of it wanting to have a period during their prep, having a retreat, say for a week, with their creative keys. Their DP, their PD, the costume designer, and just go and BE together, have space to think. To develop the look, the story, the visual side of their film and just to get to know each other. To have that time when you’re not racing into production to build up the ideas, the trust, and the collaboration for the project. Directors feel it too. And the difference between Maggie’s Plan and Little Men was that I had that time. OnLittle Men the DP came in from Spain only three weeks before production, so we didn’t have the opportunity for that same collaboration but we still made the best of it.

PDC: That very concern was something that was brought up quite a bit at the Production Design in Independent Film at Sundance. It was a question from the audience about what do PDs want to tell the directors of independent film - overwhelmingly, the panelists responded that they wanted to be more involved earlier.

Alex: Definitely, though it’s very difficult in practice. Last year I had only two weeks off all year. Which would be normal for a 9–5er, but for someone in our industry, that’s insane. Though the long prep for Maggie’s Plan was great, it was hard because I was doing that largely while I was away on other jobs. I was coming back to the city on Saturday and meeting with Rebecca on Sunday, so I’d stay up all night working on the boards, meet with her, and then go back onto my other production. It was hard. But Rebecca has a hypnotic quality about her, so you just think “I want to do all this extra work for you because I want to give you everything you want because you’re an amazing powerful force!”

PDC: Production design isn’t always recognized in a film, especially in independent cinema, and it’s often skipped in reviews completely. What do you wish people knew about designing an independent film? What would you like to change about how design is viewed in the independent filmmaking community?

Alex: I feel that a lot of the time - even on commercials. On commercials, I do my job and collaborate with the director, but on set I’m just kind of there for them. I stay out of it unless there’s something specific I can help facilitate or create. But on the Home Depot campaign I just did, everything was art department - they are selling their products, and their products are my department. For the first time, art was running the show. They realized that without the art department there wouldn’t be anything to shoot, nothing to sell, nothing to tell the story. And that’s what I wish people knew - on feature films, if we don’t show up, the actors are going to be outside with nothing or in a room with just lots of random things!

PDC: It’s tough because I generally gravitate toward bolder works with a punchy style. Though the “best production design” is what doesn’t take you out of the story, so even if it’s bold, it’s often just missed. Which is perhaps a good thing, the critics believed it instead of saying “oh god, look at that, it’s horrible.” But it’s frustrating. Why should there be an award for editing and cinematography and not production design in independent film - which is actually also the case for our silently suffering comrades in costumes. Recognize us!

Alex: Right. I read a review for Maggie’s Plan that called out the DP, the editor, and the sound designer, but there was no mention of the PD or costumes in a piece that has clear, deliberate design. Watching it as a production designer, I understood, for example, that there was a choice you made in Felicia & Tony’s apartment to have quirky non-matching curtains that affected the light beautifully. That’s a bold choice, it took effort and thought, and not a single review noticed that side of the film.

I try not to let it get to me, but it was surprising. On that film, our costumes, designed by Malgosia Turzanska, were really out there sometimes. Some reviews did make some side notes about how weird some of them were but that’s about it. I just saw a still that they are planning to use as promotion, in it Maggie is standing in front of a hideous painting we rented - hideous but a deliberate choice we made as it worked so well for that set - and it perfectly matches the colors in her costume. It’s beautiful in that moment, and we planned that. It’s not a mistake. Everything is a choice and that’s what I wish others realized.

PDC: You’ve worked in a range of genres - period pieces, thrillers, rom-coms, dramas - is there a genre that you’re still looking forward to? What about that genre offers a design challenge excites you?

Alex: I feel like I only have so many naturalistic interiors in me. I think it’s because, in part, my background is in theatre where you can really push things to the limit and suspend the disbelief. But in film you’re often trying to portray these people in a real way, and those are often the stories that are beautiful. There just aren’t that many projects that have opportunities to make something fantastic in independent cinema - not because the directors or writers can’t make those scripts, but because the budget won’t allow for it. For that reason, I would like to do bigger projects, mostly because I’m interested in having that high level of polish and sexiness. But a lot of the best scripts are some of the smaller ones, so it’s hard to reconcile that. I’m trying to do a few bigger projects, more commercials, so I have the freedom to design the scripts that speak to me the most, regardless of the budget.

But I really don’t want to discriminate against styles. In Little Men - on the surface a very naturalistic movie - we were able to find instances to include wallpaper that’s a little “out there” in a way that made sense for the story. We were able to use the dichotomy we’d established to justify it. For me, the script is so relatable because everyone has been that kid in that situation, you’ve had a friend, you’ve lost a friend. There are certain things as adults that we remember about our childhood - the smell of our grandfather’s house or the texture of that velvet couch. Or this one room in your friend’s house with crazy wallpaper that you just wished that your parents would let you put in your room. All those things are heightened because you’re a child and you're so sensitive to them. Those moments were included in the film, and you get to ask “was that crazy green and orange wallpaper really there in his room?” Maybe it was and maybe it wasn’t, but it’s part of his impression of his world at that time.

So I don’t want to discriminate. But I have to say that I do love the absurd. If I could design Britney Spears’ world tour that would be amazing. I gravitate towards scripts with bolder statements because you really get to push it, comedies are supposed to be a farce. But a naturalistic interior of someone’s house can be a challenge in its own way and that’s exciting in its own way.

PDC: Final question - is there a favorite designer/film/moment that made you want to be a PD?

Alex: Absolutely not. I come from experiential theatre and that’s always what I thought I would do. I worked on the Fantastic Mr. Fox as an intern for a while and I ended up getting hired for the last few months of the job. Though it was super cool, on that project, the hours were so long and the job was so crazy that I never wanted to work in film again! Whenever anyone asks me how I got here, I’m not sure how it happened. Film is a motley crue of scallywags who just ended up here and work really hard. Though last year, when I watched Only Lovers Left Alive andUnder the Skin - both of which I loved stylistically - I got excited to be here again. I’d like to design movies like that, so I keep going.